Posts Tagged ‘James Madison’

“Her Majesty’s government should do nothing to place in peril our opium revenues. As for preventing the manufacturing of opium, and the sale of it in China, that is far beyond your power.”*

An excerpt from Linda Jaivin‘s The Shortest History of China…

European traders had been trying to get a foothold in China for centuries. As eager as the Europeans were for Chinese tea, silk, and porcelain, the Chinese remained indifferent to European goods. The Qing restricted access to ports, confining foreign merchants to Guangzhou (Canton), from October to March. Foreign traders resented this, as well as having to work with licensed Chinese intermediaries and abide by local law. In 1793, the British sent an experienced diplomat, Lord George Macartney, to Qianlong’s court carrying a letter arguing for greater access to the empire’s markets, including a reduction in tariffs, the ability of merchants to live in China year-round, and the stationing of an ambassador in Beijing.

The eighty-year-old Qianlong agreed to receive the Englishman at his imperial hunting lodge at Chéngdé, northeast of Beijing. The protocol of an imperial audience demanded a kowtow. Macartney refused, instead bowing on one knee before Qianlong, just as he did with his own sovereign, King George III. Qianlong received him courteously anyway, but once Macartney left and his letter was translated, Qianlong instructed his ministers to bolster the Qing’s coastal defenses, predicting that England, ‘fiercer and stronger than other countries in the Western Ocean,’ might ‘stir up trouble.’ To Macartney he prefaced his reply by saying that the Qing had everything it needed in abundance: ‘I set no value on objects strange or ingenious, and have no use for your country’s manufactures.’

The British East India Company, which enjoyed a British monopoly on East Asian trade, had something for which at least some Chinese had use: opium, grown in British-controlled India. Opium was already cultivated in China, but in small quantities — soldiers and manual laborers relied on it for pain relief, and some of the idle rich smoked it for pleasure. In 1729, the British sold two hundred chests of opium into China, each containing almost sixty kilograms of the drug. In 1790, three years before Macartney’s visit, they sold 4,054 chests. That number increased steadily.

Qianlong retired in 1796 in a gesture of filial piety, not wanting his reign to outlast that of his revered grandfather, Kangxi. This left the problem of opium to his successor, Jiāqìng (r. 1796-1820).

In 1815, the British sent another envoy, Lord Amherst, to Beijing. Jiāqìng expelled him after another tussle over the kowtow.

Opium addiction began to damage the fabric of Chinese society. The illegal trade fostered corruption, and silver drained from the imperial coffers. Debate raged in the court of Jiāqìng and his successor, Dàoguāng (r. 1821-1850), over whether to legalize opium — encouraging domestic production and limiting trade-related corruption — or ban it. In 1838, Daoguang decided on prohibition. In March 1839, the emperor sent the official Lín Zéxú (1785-1850) to Guangzhou, the hub of the opium trade, to implement the ban. By July, Lin had arrested thousands of addicts and confiscated almost twenty-three thousand kilos of opium, as well as seventy thousand pipes.

Lín Zéxú demanded that the 350 or so foreign traders in Guangzhou surrender their opium. As tensions rose, he locked them in their warehouses. Chinese soldiers blew horns and banged gongs to increase the pressure on them. It took six weeks, but the foreigners handed over twenty thousand chests. Now in possession of almost 1.4 million kilos of opium, Lín Zéxú had it mixed with water, salt, and lime and flushed out to sea.

In response, British warships blockaded the entrance to Guangzhou’s harbor, smashed through Chinese defenses, and captured ports including Shanghai and Ningbo, blocking maritime traffic on the Grand Canal and lower Yangtze. This became known as the First Opium War.

Under duress, the Qing signed the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842, which granted the British access to Guangzhou, Shanghai, and three other ‘treaty ports.’ It also ceded the island of Hong Kong — ‘fragrant port,’ named for the spice trade — to the British in perpetuity. (The British foreign secretary at the time, Lord Palmerston, questioned the wisdom of acquiring ‘a barren island with hardly a House upon it’ that would never become a great ‘Mart of Trade.’) It imposed indemnities on the Qing totaling twenty-one million silver dollars. The United States, France, and other nations piled on with their own demands, including ‘extraterritoriality’ exemption from local justice for foreigners who committed crimes in China. Chinese law would not apply within ‘concessions’ those parts of the treaty ports controlled by foreign powers. These agreements were the first of what are called the Unequal Treaties, beginning a century of China’s humiliation at the hands of various imperialist powers. They heralded the beginning of the end, not just of the Qing, but of the dynastic system by which China had been ruled for thousands of years…

Via the invaluable Delancyplace (@delanceyplace): “The Opium Wars.”

* Lord Ellenborough, 1843

###

As we contemplate colonialism, we might recall that it was on this date in 1812 that President James Madison signed the declaration of war against Great Britain that formally launched the War of 1812.

Three U.S. incursions into Canada launched in 1812 and 1813 had been handily turned back by the British despite the fact that the bulk of British force was tied up in an unpleasantness with the Emperor of France and his troops. But the decline of Napoleon’s strength freed the English to devote more resources to the West… leading to the 1814 burning of the White House, the Capital, and much of the rest of official Washington by British soldiers (retaliating for the U.S. burning of some official buildings in Canada). Still, by the end of 1814 a combination of naval and ground victories by the Americans had driven the British back to Canada, and on December 14, 1814 the Treaty of Ghent, ending the war, was signed… sadly for the British, word of the accord did not reach troops on the Gulf Coast in time to head off an attack (on January 8, 1815) on New Orleans– which was turned back by American forces led by Andrew Jackson. Jackson became a national hero, who rode his fame to the (rebuilt) White House; Johnny Horton got a Number One record out of it (Billboard Hot 100, 1959)… and the English had to console themselves with their victory at Waterloo later that year– on this date in 1815…

“Humanity’s 21st century challenge is to meet the needs of all within the means of the planet”*…

One evening in December, after a long day working from home, Jennifer Drouin, 30, headed out to buy groceries in central Amsterdam. Once inside, she noticed new price tags. The label by the zucchini said they cost a little more than normal: 6¢ extra per kilo for their carbon footprint, 5¢ for the toll the farming takes on the land, and 4¢ to fairly pay workers. “There are all these extra costs to our daily life that normally no one would pay for, or even be aware of,” she says.

The so-called true-price initiative, operating in the store since late 2020, is one of dozens of schemes that Amsterdammers have introduced in recent months as they reassess the impact of the existing economic system. By some accounts, that system, capitalism, has its origins just a mile from the grocery store. In 1602, in a house on a narrow alley, a merchant began selling shares in the nascent Dutch East India Company. In doing so, he paved the way for the creation of the first stock exchange—and the capitalist global economy that has transformed life on earth. “Now I think we’re one of the first cities in a while to start questioning this system,” Drouin says. “Is it actually making us healthy and happy? What do we want? Is it really just economic growth?”

In April 2020, during the first wave of COVID-19, Amsterdam’s city government announced it would recover from the crisis, and avoid future ones, by embracing the theory of “doughnut economics.” Laid out by British economist Kate Raworth in a 2017 book, the theory argues that 20th century economic thinking is not equipped to deal with the 21st century reality of a planet teetering on the edge of climate breakdown. Instead of equating a growing GDP with a successful society, our goal should be to fit all of human life into what Raworth calls the “sweet spot” between the “social foundation,” where everyone has what they need to live a good life, and the “environmental ceiling.” By and large, people in rich countries are living above the environmental ceiling. Those in poorer countries often fall below the social foundation. The space in between: that’s the doughnut.

Amsterdam’s ambition is to bring all 872,000 residents inside the doughnut, ensuring everyone has access to a good quality of life, but without putting more pressure on the planet than is sustainable. Guided by Raworth’s organization, the Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL), the city is introducing massive infrastructure projects, employment schemes and new policies for government contracts to that end. Meanwhile, some 400 local people and organizations have set up a network called the Amsterdam Doughnut Coalition—managed by Drouin— to run their own programs at a grassroots level…

You’ve heard about “doughnut economics,” a framework for sustainable development; now one city, spurred by the pandemic, is putting it to the test: “Amsterdam Is Embracing a Radical New Economic Theory to Help Save the Environment. Could It Also Replace Capitalism?“

* Kate Raworth, originator of the Doughnut Economics framework

###

As we envisage equipoise, we might recall that it was on this date in 1791 that President George Washington signed the Congressional legislation creating the “The President, Directors and Company, or the Bank of the United States,” commonly known as the First Bank of the United States. While it effectively replaced the Bank of North America, the nation’s first de facto central bank, it was First Bank of the United States was the nation’s first official central bank.

The Bank was the cornerstone of a three-part expansion of federal fiscal and monetary power (along with a federal mint and excise taxes) championed by Alexander Hamilton, first Secretary of the Treasury– and strongly opposed by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, who believed that the bank was unconstitutional, and that it would benefit merchants and investors at the expense of the majority of the population. Hamilton argued that a national bank was necessary to stabilize and improve the nation’s credit, and to improve handling of the financial business of the United States government under the newly enacted Constitution.

History might suggest that both sides were correct.

“Caveat lector”*…

* “Let the reader beware,” Latin phrase

###

As we interrogate our sources, we might recall that it was on this date in 1789 that Representative (later, President) James Madison introduced nine amendments to the U.S. Constitution in the House of Representatives; subsequently, Madison added three more, ten of which (including 7 of his original nine) became the Bill of Rights.

Madison, often called “the Father of the Constitution,” created the amendments to appease anti-Federalists on the heels of the oftentimes bitter 1787–88 battle over ratification of the U.S. Constitution– in the drafting of which he had also played a central role.

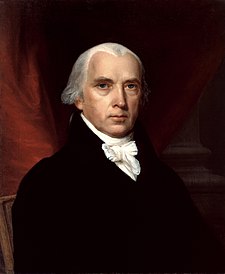

Madison

Time’s past..

From the inquisitive folks over at Reason, an amusing, and at the same time provocative, look at “The Top 10 Most Absurd Time Covers of The Past 40 Years”

Consider for example:

Oh, Just Settle Down: The crack kids myth has been extensively debunked, most recently in the January 2009 New York Times article “Crack Babies: The Epidemic That Wasn’t.” The Times quoted researchers who’ve been following the so-called crack generation of kids, and they’re finding the effects to be minor and subtle, and virtually indistinguishable from other problems that kids of crack mothers might experience, such as unstable families and poor parenting. Persistent scare stories from Time and other media outlets (including The New York Times itself) made “crack babies” a nationwide moral panic, inspiring a racially fueled push for stricter drug laws. As the Times article explains, the crack baby myth itself may now be doing harm to otherwise normal kids: “[C]ocaine-exposed children are often teased or stigmatized if others are aware of their exposure. If they develop physical symptoms or behavioral problems, doctors or teachers are sometimes too quick to blame the drug exposure and miss the real cause, like illness or abuse.”

For similar treatments of Mr. Luce’s Magazine’s hysteria over satanism, porn, crack, and Pokemon see here.

As we contemplate the substitution of hyperbole for reportage in so much– too much– of the mainstream media, we might recall that it was on this date in 1812 that President James Madison signed the declaration of war against Great Britain that formally launched the War of 1812. Three U.S. incursions into Canada launched in 1812 and 1813 were all handily turned back by the British despite the fact that the bulk of British force was tied up in an unpleasantness with the Emperor of France and his troops. But the decline of Napoleon’s strength freed the English to devote more resources to the West… leading to the 1814 burning of the White House, the Capital, and much of the rest of official Washington by British soldiers (retaliating for the U.S. burning of some official buildings in Canada. Still, by the end of 1814 a combination of naval and ground victories by the Americans had driven the British back to Canada, and on December 14, 1814 the Treaty of Ghent, ending the war, was signed… sadly for the British, word of the accord did not reach troops on the Gulf Coast in time to head off an attack (on January 8, 1815) on New Orleans– which was turned back by American forces led by Andrew Jackson. Jackson became a national hero, who rode his fame to the (rebuilt) White House; Johnny Horton got a Number One record out of it (Billboard Hot 100, 1959)… and the English had to console themselves with their victory at Waterloo later that year– on this date in 1815…

You must be logged in to post a comment.