Posts Tagged ‘cartography’

“We’re all pilgrims on the same journey but some pilgrims have better road maps”*…

Tis the season for road trips. These days, we tend to navigate via Google Maps; but for centuries, travelers relied on road atlases. From the Bodleian Library‘s Map Room, a wonderful example from the 18th century…

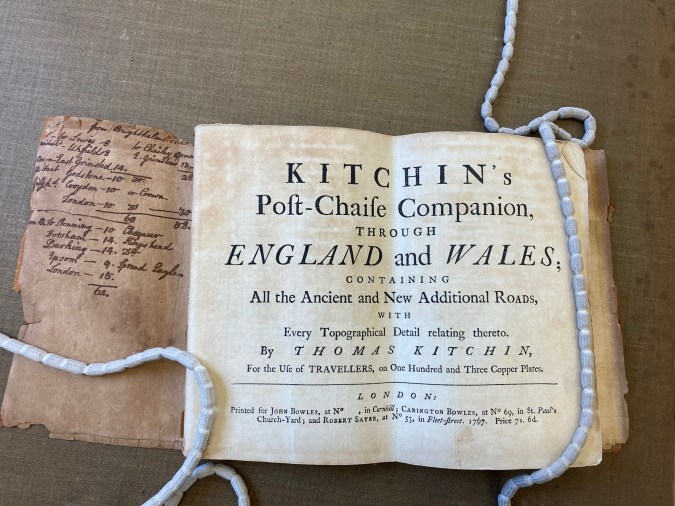

As a general rule we do not fold our atlases in half. It would be bad for them, and probably quite difficult. This is a rare example of an atlas that was designed to be folded in half.

It’s an early road atlas to be carried while traveling. When the soft, rather tattered brown leather covers are opened, it reveals that a previous owner has made some notes of place names and distances in the inside of the cover.

The book itself could be folded or rolled, making it smaller and more portable. It is Thomas Kitchin’s Post-chaise companion, and dates from 1767. It has clearly grown accustomed to being folded in half, as can be seen from the weights required to hold it open for photography:

The very earliest road atlases date from the seventeenth century. Previously travellers relied on road books, lists of names that would enable them to ask the way from one town to the next. Arguably the first road atlas was produced by Matthew Simmons in the 1630s, with triangular distance tables (like those sometimes found in modern road atlases) and very tiny maps. The big innovation was John Ogilby’s Britannia in 1675, which used strip maps to show the major roads throughout Great Britain in unprecedented detail; this design continued to be copied for over a century, as can be seen here. Britannia was however a large volume, too bulky to transport easily.

Perhaps surprisingly, it was around fifty years after the publication of Britannia before smaller, more portable versions were produced, and then rival versions by three different publishers appeared around the same time in the 1720s; one of these, by Emanuel Bowen, was reissued in multiple editions into the 1760s. Thomas Kitchin, who produced this work, had been apprenticed to Bowen, and had married Bowen’s daughter before setting up as an independent mapmaker, embarking on a long, prolific and successful career, and being appointed Hydrographer to George III.

Although many road atlases of this period survive, the binding is what makes this one unusual. Its appearance caused a certain amount of excitement in the Map Room as some of us had heard of road atlases being made to this design, but had never seen one before. Unsurprisingly the soft backed versions are less likely to have survived, being less robust and more heavily used than the hardbacks. The fact that this one has the notes relating to a previous owner’s journeys makes it additionally interesting…

A traveler’s companion: “On the road,” at @bodleianlibs.

* Nelson DeMille

###

As we plan a route, we might ponder a very specific path, recalling that today– and every June 16– is Bloomsday, a commemoration and celebration of the life of Irish writer James Joyce, during which the events of his novel Ulysses (a modern classic set on this date in 1904) are relived: Leopold Bloom goes about Dublin, James Joyce’s immortalization of his first outing with Nora Barnacle, the woman who would eventually become his wife.

The first Bloomsday was observed on the 50th anniversary of the events in the novel, in 1954, when John Ryan (artist, critic, publican and founder of Envoy magazine) and the novelist Brian O’Nolan organized what was to be a daylong pilgrimage along the Ulysses route. They were joined by Patrick Kavanagh, Anthony Cronin, Tom Joyce (a dentist who, as Joyce’s cousin, represented the family interest), and AJ Leventhal (a lecturer in French at Trinity College, Dublin).

“Being so many different sizes in a day is very confusing”*…

Maps are crucial– and they’re also often crucially wrong… or at least misleading. Any attempt to reduce our 3-D world in 2-D results in distortion.

It is hard to represent our spherical world on flat piece of paper. Cartographers use something called a “projection” to morph the globe into 2D map. The most popular of these is the Mercator projection.

Every map projection introduces distortion, and each has its own set of problems. One of the most common criticisms of the Mercator map is that it exaggerates the size of countries nearer the poles (US, Russia, Europe), while downplaying the size of those near the equator (the African Continent). On the Mercator projection Greenland appears to be roughly the same size as Africa. In reality, Greenland is 0.8 million sq. miles and Africa is 11.6 million sq. miles, nearly 14 and a half times larger.

This app was created by James Talmage and Damon Maneice. It was inspired by an episode of The West Wing and an infographic by Kai Krause entitled “The True Size of Africa“. We hope teachers will use it to show their students just how big the world actually is…

The world as it actually is: “The True Size,” an interactive tool that let’s one compare the real scale of any two countries.

Apposite: “Animated Map: Where Are the Largest Cities Throughout History?” (with thanks to friend JA)

* Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

###

As we muse on measurement, we might recall that it was on this date in 1513 that Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de Leon came ashore and claimed “La Florida” [the “land of flowers”] for Spain. While it has long been accepted that de Leon landed with his three caravels near St. Augustine and became the first European of record to see the peninsula, scholars have recently challenged details of that historical account, suggesting that he actually beached near Melbourne.

In any event, he went on to map the Atlantic coast down to the Florida Keys and north along the Gulf coast; historian John Reed Swanton believed that he sailed perhaps as far as Apalachee Bay on Florida’s western coast. Though popular lore has it that he was searching for the Fountain of Youth, there is no contemporary evidence to support the story, which most modern historians consider a myth.

“I was a peripheral visionary. I could see the future, but only way off to the side.”*…

As Niels Bohr said, “prediciton is hard, especially about the future.” Still, we can try…

While the future cannot be predicted with certainty, present understanding in various scientific fields allows for the prediction of some far-future events, if only in the broadest outline. These fields include astrophysics, which studies how planets and stars form, interact, and die; particle physics, which has revealed how matter behaves at the smallest scales; evolutionary biology, which studies how life evolves over time; plate tectonics, which shows how continents shift over millennia; and sociology, which examines how human societies and cultures evolve.

The far future begins after the current millennium comes to an end, starting with the 4th millennium in 3001 CE, and continues until the furthest reaches of future time. These timelines include alternative future events that address unresolved scientific questions, such as whether humans will become extinct, whether the Earth survives when the Sun expands to become a red giant and whether proton decay will be the eventual end of all matter in the Universe…

A new pole star, the end of Niagara Falls, the wearing away of the Canadian Rockies– and these are just highlights from the first 50-60 million years. Read on for an extraordinary outline of what current science suggests is in store over the long haul: “Timeline of the far future,” a remarkable Wikipedia page.

Related pages: List of future astronomical events, Far future in fiction, and Far future in religion.

* Steven Wright

###

As we take the long view, we might send grateful birthday greetings to the man who “wrote the book” on perspective (a capacity analogically handy in the endeavor featured above), Leon Battista Alberti; he was born on this date in 1404. The archetypical Renaissance humanist polymath, Alberti was an author, artist, architect, poet, priest, linguist, philosopher, cartographer, and cryptographer. He collaborated with Toscanelli on the maps used by Columbus on his first voyage, and he published the the first book on cryptography that contained a frequency table.

But he is surely best remembered as the author of the first general treatise– De Pictura (1434)– on the the laws of perspective, which built on and extended Brunelleschi’s work to describe the approach and technique that established the science of projective geometry… and fueled the progress of painting, sculpture, and architecture from the Greek- and Arabic-influenced formalism of the High Middle Ages to the more naturalistic (and Latinate) styles of Renaissance.

“If the map doesn’t agree with the ground the map is wrong”*…

Maps from hundreds of years ago can be surprisingly accurate… or they can just be really, really wrong. Weird maps from history invent lands wholesale, distort entire continents, or attempt to explain magnetism planet-wide. Sometimes the mistakes had a surprising amount of staying power, too, getting passed from map to map over the course of years while there was little chance to independently verify…

Gerardus Mercator, creator of everyone’s favorite map projection, didn’t know what the north pole looked like. No one in his time really did. But they knew that magnetic compasses always pointed north, and so a theory developed: the north pole was marked by a giant magnetic black-rock island.

He quotes a description of the pole in a letter: “In the midst of the four countries is a Whirl-pool, into which there empty these four indrawing Seas which divide the North. And the water rushes round and descends into the Earth just as if one were pouring it through a filter funnel. It is four degrees wide on every side of the Pole, that is to say eight degrees altogether. Except that right under the Pole there lies a bare Rock in the midst of the Sea. Its circumference is almost 33 French miles, and it is all of magnetic Stone (…) This is word for word everything that I copied out of this author [Jacobus Cnoyen] years ago.”

Mercator was not the first or only mapmaker to show the pole as Rupes Nigra, and the concept also tied into fiction and mythology for a while. The idea eventually died out, but people explored the Arctic in hopes of finding a passage through the pole’s seas for years before the pole was actually explored in the 1900s…

See five more confounding charts at “The Weird History of Extremely Wrong Maps.”

And for fascinating explanations of maps with intentional “mistakes,” see: “MapLab: The Legacy of Copyright Traps” and “A map is the greatest of all epic poems.”

* Gordon Livingston

###

As we find our way, we might spare a thought for Thomas Doughty; he was beheaded on this date in 1578. A nobleman, soldier, scholar, and personal secretary of Christopher Hatton, Doughty befriended explorer and state-sponsored pirate Francis Drake, then sailed with him on a 1577 voyage to raid Spanish treasure fleets– a journey that ended for Doughty in a shipboard trial for treason and witchcraft, and his execution.

Although some scholars doubt the validity of the charges of treason, and question Drake’s authority to try and execute Doughty, the incident set an important precedent: according to a history of the English Navy, To Rule the Waves: How the British Navy Shaped the Modern World by Arthur L. Herman, Doughty’s execution established the idea that a ship’s captain was its absolute ruler, regardless of the rank or social class of its passengers.

“Without geography you’re nowhere”*…

Finding meaning in maps…

You may not know it, but you’ve probably seen the Valeriepieris circle – it’s that circle on a map of the world, alongside the text ‘There are more people living inside this circle than outside of it’. The name ‘Valeriepieris’ is from the Reddit username of the person who posted it and in 2015 the circle was looked at in more detail by Danny Quah of the London School of Economics under the heading ‘The world’s tightest cluster of people‘. But of course it’s not actually a circle because it wasn’t drawn on a globe and it’s also a bit out of date now so I thought I’d look at this topic because I like global population density stuff. I’ll begin by posting a map of what I’m calling ‘The Yuxi Circle’ and then I’ll explain everything else below that – with lots of maps. As in the original circle, I decided to use a radius of 4,000 km, or just under 2,500 miles. Why Yuxi? Well, out of all the cities I looked at (more than 1,500 worldwide), Yuxi had the highest population within 4000km – just over 55% of the world’s population as of 2020…

More– including fascinating comparisons– at “The Yuxi Circle,” from Alasdair Rae (@undertheraedar)

* Jimmy Buffett

###

As we ponder population, we might recall that it was on this date in 1995 that the day-time soap opera As The World Turns aired its 10,000th episode. Created by Irna Phillips, it aired for 54 years (from April 2, 1956, to September 17, 2010); its 13,763 hours of cumulative narrative gave it the longest total running time of any television show. Actors including, Marissa Tomei, Meg Ryan, Amanda Seyfried, Julianne Moore, and Emmy Rossum all appeared on the series.

You must be logged in to post a comment.