Posts Tagged ‘lexicon’

“I was reading the dictionary. I thought it was a poem about everything.”*…

That seminal semanticist Samuel Johnson suggested, “dictionaries are like watches, the worst is better than none and the best cannot be expected to go quite true.” From “unabridged” to “slanguage,” Madeline Kripke’s library of lexicons is a logophile’s heaven (or hell)…

Madeline Kripke’s first dictionary was a copy of Webster’s Collegiate that her parents gave her when she was a fifth grader in Omaha in the early 1950s. By the time of her death in 2020, at age 76, she had amassed a collection of dictionaries that occupied every flat surface of her two-bedroom Manhattan apartment—and overflowed into several warehouse spaces. Many believe that this chaotic, personal library is the world’s largest compendium of words and their usage.

“We don’t really know how many books it is,” says Michael Adams, a lexicographer and chair of the English department at Indiana University Bloomington. More than 1,500 boxes, with vague labels such as “Kripke documents” or “Kripke: 17 books,” arrived at the school’s Lilly Library on two tractor-trailers in late 2021. The delivery was accompanied by a nearly 2,000-page catalog detailing some 6,000 volumes. But that’s only a fraction of the total. In summer 2023, the library hired a group of students to simply open each box and list its contents. By the fall, their count stood at about 9,700. “And they’ve got a long way to go,” says Adams. “20,000 sounds like a pretty good estimate.”

…

“This is my favorite wall,” Madeline Kripke told Narratively reporter Daniel Kreiger when he visited her West Village apartment in 2013. She shined a flashlight on glass-fronted shelves jammed with dictionaries full of the slanguage and cryptolect of small and likely overlooked communities. Kreiger listed some of the groups represented at that time, among them cowboys and flappers, mariners and gamblers, soldiers, circus workers, and thieves.

Among the first tomes Adams pulled from the boxes was a well-known example of the slang genre: The Canting Academy. This 17th-century dictionary by Richard Head is a guide to “cant,” the jargon of London’s criminal class or, as the subtitle to the second edition puts it, “The Mysterious and Villainous Practices Of that wicked Crew, commonly known by the Names of Hectors, Treppaners, Gults, &c.” (Adams wonders if a first edition is also hidden in the banker’s boxes.) With The Canting Academy, one can learn to translate the cant of the “priggs” (“all sorts of thieves”) to English: “lour” to “money,” “pannam” to “bread,” “lage” to “water.” Most of the language is indecipherable without this key, but Adams notes some usages that are common today. “To plant” something is, in centuries-old cant or modern-day English, “to lay, place, or hide.”

…

Much of what Adams has unpacked has a far less storied (and pricey) past, but, he says, the quirky and unexpected volumes in Kripke’s collection might be the most valuable to future lexicographers and historians. A bright red pamphlet with a doodle of heart on the cover might seem disposable, but it is an artifact of a particular place and time, Adams says. “Dictionaries are made by people, so they’re not just language books,” he says, “they’re culture books.”

Printed in 1962 as a marketing tool for a CBS sitcom, that slim pamphlet featuring a big heart around the faces of two 20-something actors is Dobie Gillis: Teenage Slanguage Dictionary, filled with “teen-age antics and terms.” It’s the type of thing that might have been stuffed into a cereal box or inserted in a teen magazine, says Adams. “I’m pretty sure that most people threw the copy they had away, and so this one is a fairly rare item that says something important about the representation of teen language and culture in the 1950s and 1960s.” Thanks to Kripke’s copy we know that this, at least according to the marketers behind The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis, was the era of the “keen teen” (“well-liked person”), the “cream puff” (“conceited person”), the “meatball” (“a dull guy”), and the “mathematician” (“teen who can put two and two together and get SEX”).

…

Kripke—“the mistress of slang,” in the words of one colleague—dedicated decades of her life to curating this collection of words, including countless ones we might like to forget. When she passed away without a will, the fate of her overwhelming library, plus a trove of documents on the history of dictionary making, was uncertain. Auctioning it off in lots could have brought the highest bids, but Kripke’s family worked in conjunction with the lexicographic community to preserve what Adams calls “her legacy.” That it was ultimately purchased in total by Indiana University Bloomington, a state university that committed to making the works accessible to the public, seems in keeping with the way Kripke herself viewed the collection, as a resource for the curious.

“You would go to see her in her Village apartment, and it was filled from top to bottom and side to side with books,” Adams says. It would have taken some digging but, “she would have the book that you need to see out for you and always some other specimens, too.”…

“The Low Down on the Greatest Dictionary Collection in the World,” in @atlasobscura.

* Steven Wright

###

As we look it up, we might recall that it was on this date in 1660, at Gresham College in London, that twelve men, including Christopher Wren, Robert Boyle, John Wilkins, and Sir Robert Moray decided to found a “Colledge for the Promoting of Physico-Mathematicall Experimentall Learning” to promote “experimental philosophy” (which became science-as-we-know-it). Six months later, Robert Hooke‘s first publication, a pamphlet on capillary action, was read to the group.

The Society subsequently petitioned King Charles II to recognize it and to make a royal grant of incorporation. The Royal Charter, which was passed in July, 1662 created the Royal Society of London.

In 1665, the society introduced the world’s first journal exclusively devoted to science in 1665, Philosophical Transactions (and in so doing originated the peer review process now widespread in scientific journals). Its founding editor was Henry Oldenburg, the society’s first secretary. It remains the oldest and longest-running scientific journal in the world.

“Slang is a language that rolls up its sleeves, spits on its hands and goes to work”*…

For example…

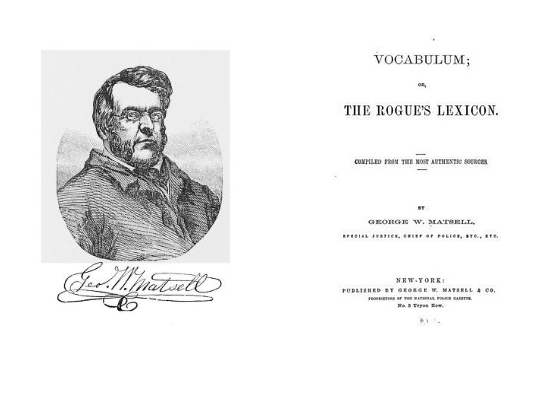

The slang of 19th century scoundrels and vagabonds: browse it in full at invaluable Internet Archive, “Vocabulum; or, The Rogue’s Lexicon.”

* Carl Sandburg

###

As we choose our words, we might send fashionable birthday greetings to George Bryan “Beau” Brummell; he was born on this date in 1778. An important figure in Regency England (a close pal of the Prince Regent, the future King George IV), he became the the arbiter of men’s fashion in London in the territories under its cultural sway.

Brummell was remembered afterwards as the preeminent example of the dandy; a whole literature was founded upon his manner and witty sayings, e.g. “Fashions come and go; bad taste is timeless.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.