Posts Tagged ‘epidemiology’

“Eventually, all things merge into one, and a river runs through it”*…

Cartographer Daniel Huffman has created a series of maps in which American river systems are visualized as subway maps (specifically, in the manner of Harry Beck’s 1930s London Tube maps), with nodes representing connections between streams and tributaries.

Huffman strikes a particular chord in the map-lover’s heart. On an Internet brimming with sleek, sharp geo-visualizations, Huffman’s maps offer a sweetly idiosyncratic view of the world. The signatures of historic figures turn into street vectors. Oregon’s wine country gets the ‘90s computer-game treatment. A simple bike path becomes a work of calligraphy.

“What it really probably comes down to is a desire to do things differently than others,” he says in an email. “I crave variety, and so it often leads me to thinking of weird ideas and saying, ‘I wonder if I can do X[.]’”

Lately, a trend has emerged out of Huffman’s impulses towards novelty—an idea he calls “Modern Naturalism,” in which his maps present natural features in the type of “highly-abstracted, geometrically precise visual language that we often apply to the constructed world on maps,” according to his website…

More on Huffman and his marvelous maps at “When Rivers Look Like Subway Systems.”

* Norman Maclean, A River Runs Through It and Other Stories

###

As we hop onto our rafts, we might send healing birthday greetings to Florence Nightingale, born on this date in 1820. Famed for her work as a nurse in the Crimean War, she went on to found training facilities and nursing homes– pioneering both medical training for women and what is now known as Social Entrepreneuring. Less well-known are Nightingale’s contributions to epidemiology, statistics, and the visual communication of data in the field of public health. Always good at math, she pioneered the use of the polar area chart (the equivalent to a modern circular histogram or rose diagram) and popularized the pie chart (which had been developed in 1801 by William Playfair). Nightingale was elected the first female member of the Royal Statistical Society, and later became an honorary member of the American Statistical Association.

“Diagram of the causes of mortality in the army in the East” by Florence Nightingale, an example of the the polar area diagram (AKA, the Nightingale rose diagram)

The Joys of Knowing History, Illustrated…

from “Krazy Kat and Ignatz Mouse at the Circus” (click here to view)

from “Krazy Kat and Ignatz Mouse at the Circus” (click here to view)

Animated drawings were introduced to film a full decade after George Méliès had demonstrated in 1896 that objects could be set in motion through single-frame exposures. J. Stuart Blackton’s 1906 animated chalk experiment Humorous Phases of Funny Faces was followed by the imaginative works of Winsor McCay, who made between four thousand and ten thousand separate line drawings for each of his three one-reel films released between 1911 and 1914. Only in the half-dozen years after 1914, with the technical simplifications (and patent wars) involving tracing, printing, and celluloid sheets, did animated cartoons become a thriving commercial enterprise. This period–upon which this collection concentrates–brought assembly-line standardization but also some surprisingly surreal wit to American animation. The twenty-one films (and two Winsor McCay fragments) in this collection, all from the Library of Congress holdings, include clay, puppet, and cut-out animation as well as pen drawings. Beyond their artistic interest, these tiny, often satiric, films tell much about the social fabric of World War I-era America.

See these and other important– and enormously entertaining– animated films from 1900-1921 at the Library of Congress’ “Origins of American Animation“– Krazy Kat, Keeping Up With the Joneses, The Katzenjammer Kids, and more than a dozen other joys (that don’t start with “K”).

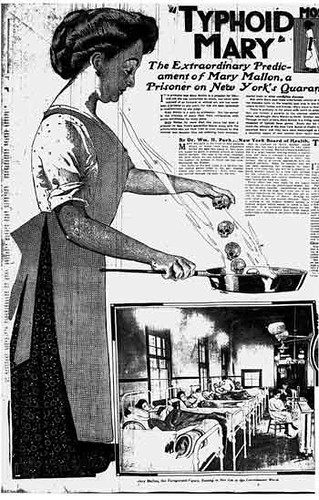

As we debate whether Windsor McCay or George Herriman was the greater genius, we might recall that it was on this date in 1938 that Mary Mallon– “Typhoid Mary”– died of a stroke on North Brother Island, where she he had been quarantined since 1915. She was the first person in the United States identified as an asymptomatic carrier of the pathogen associated with typhoid fever… before which, she inadvertently spread typhus for years while working as a cook in the New York area.

You must be logged in to post a comment.