Posts Tagged ‘basketball’

“When you’re accustomed to wealth, you don’t show it, right? That’s why the white kids in school could wear bummy sneakers”*…

The Converse Rubber Shoe Company’s non-skid All Star sneakers, from 1923

It was not until the 1920s that industrialization made sneakers widely available and affordable. Once an emblem of privileged leisure on the tennis court, the canvas-and-rubber high-top adapted to the new, egalitarian team sport of basketball. The Converse Rubber Shoe Company—founded in 1908 as a producer of galoshes—introduced its first basketball shoe, the All Star, in 1917. In a stroke of marketing genius, Converse enlisted basketball coaches and players as brand ambassadors, including Chuck Taylor, the first athlete to have a sneaker named after him.

Politics, however, fueled the rise of sneakers as much as athletics. As [Elizabeth Semmelhack, curator of the traveling exhibtion, Out of the Box: The Rise of Sneaker Culture] explained, “the fragile peace of World War I increased interest in physical culture, which became linked to rising nationalism and eugenics. Countries encouraged their citizens to exercise not just for physical perfection but to prepare for the next war. It’s ironic that the sneaker became one of the most democratized forms of footwear at the height of fascism.” Mass exercise rallies were features of fascist life in Germany, Japan, and Italy. But sneakers could also represent resistance. Jesse Owens’ dominance at the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games stung the event’s Nazi hosts even more because he trained in German-made Dassler running shoes. (The company was later split between the two Dassler brothers, who renamed their shares Puma and Adidas).

When the U.S. government rationed rubber during World War II, sneakers were exempted following widespread protests. The practical, inexpensive, and casual shoe had become central to American identity, on and off the playing field. The growing influence of television in the 1950s created two new cultural archetypes: the celebrity athlete and the teenager. James Dean effectively rebranded Chuck Taylors as the footwear of choice for young rebels without a cause.

Sneakers became footnotes in the history of the Civil Rights movement. In 1965, I Spy was the first weekly TV drama to feature a black actor—Bill Cosby—in a lead role. His character, a fun-loving CIA agent going undercover as a tennis coach, habitually wore white Adidas sneakers, easily identifiable by their prominent trio of stripes. This updated gumshoe alluded to the “sneaky” origins of sneakers, while also serving as shorthand for new-school cool. Sneakers played a more explicit part at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City, where American gold medalist sprinter Tommie Smith and his bronze medal-winning teammate, John Carlos, removed their Puma Suedes and mounted the medal podium in their stocking feet, to symbolize African-American poverty, their heads lowered and black-gloved fists raised in a Black Power salute. The ensuing controversy didn’t hurt the success of the Suede, still in production today.

Around the same time, the jogging craze necessitated low-rise, high-tech footwear that bore little resemblance to the familiar canvas-and-rubber basketball high-top. But these state-of-the-art shoes weren’t made for running alone; they were colorful, covetable fashion statements. In 1977, Vogue declared that “real runner’s sneakers” had become status symbols, worn by famous non-athletes like Farrah Fawcett and Mick Jagger. Instead of one pair of sneakers, people needed a whole wardrobe of them, custom-made for different activities—or genders. Sneaker companies embraced women’s liberation as a promotional ploy, advertising shoes specifically designed for female bodies and lifestyles.

As the suburbs became overrun with joggers, America’s cities saw a rise in basketball players, particularly New York, where a bold new style of play transformed the game into a spectacle of masculine swagger. Like break dancing, schoolyard basketball ritualized a competitive physicality, which bled into mainstream (white) culture. “In the 1970s, New Yorkers in the basketball and hip-hop community changed the perception of sneakers from sports equipment to tools for cultural expression,” the sneaker historian Bobbito Garcia explains in the Out of the Box catalogue. “The progenitors of sneaker culture were predominantly … kids of color who grew up in a depressed economic era.” The 2015 documentary Fresh Dressed highlighted the prominent role of sneakers in the history of black urban culture—and its appropriation by whites.

The humble canvas sneaker, since the ’60s supplanted in the sports world by more ergonomic designs in futuristic materials, found new life as an everyday shoe. Over the next few decades, canvas sneakers came to embody youthful rebellion as much as athleticism. Beatniks, rockers, and skateboarders adopted them because they were cheap, anonymous, and authentic—not necessarily because they were comfortable or cool. Converse, Keds, and Vans got their street cred not from sports stars, but from the Ramones, Sid Vicious, and Kurt Cobain. (In 2008, Converse angered Nirvana fans by issuing special-edition high-tops tastelessly covered with sketches and scribbles from the late frontman’s diary.) The All Star, formerly available only in black or white, suddenly appeared in a rainbow of fashion colors.

The ascent of aerobics in the early ’80s left Nike, known for its jogging shoes, struggling to adjust. In February 1984, the company reported its first-ever quarterly loss, but that same year Nike signed basketball rookie Michael Jordan to an endorsement deal—arguably the birth of modern sneaker culture. Jordan wore his signature Air Jordans in NBA games, in defiance of league rules. Nike happily paid his $5,000-per-game fine, while airing ads declaring: “The NBA can’t keep you from wearing them.” And so when the first Air Jordans hit stores in 1985, the sneakers carried with them a distinct whiff of sticking it to The Man, despite their $65 price tag. But not everyone wanted to be like Mike. As Jordan grew rich off of his Nike partnership, he was accused of staying silent on political issues affecting the African American community. “Republicans buy sneakers, too,” he allegedly responded.

The growing popularity of sneakers on both sides of the political divide set the stage for a raging culture war over the shoes’ ties to criminality, or lack thereof. In “My Adidas” (1986)—one of many hip-hop sneaker shout-outs—Run-DMC defended their laceless Adidas Superstars against sneakers’ thuggish image as “felon shoes,” rapping: “I wore my sneakers, but I’m not a sneak.” (The band was rewarded with an Adidas endorsement deal, a first for a musical group.)

But Nike’s all-white Air Force 1 sneaker, released in the same year as “My Adidas,” may have merited the name of “felon shoes.” Having enough money to step out in “fresh”—i.e., pristine and unscuffed—Air Force 1s became a point of pride among street drug dealers. “Like the complicated icon of the cowboy, the drug dealer was also a symbol of rugged individualism whose fashion was hypermasculine and easily marketed … in ways that capitalized on both its American-ness and its exoticism simultaneously,” Semmelhack writes in the exhibition catalogue. The AF1, far from a public-relations disaster, became an instant classic…

Athletic shoes, a $65 billion global market, are about much more than athletics—conveying ideas about national identity, class, race, and other forms of social meaning: “Sneakers Have Always Been Political Shoes.”

See also “A Brief History of America’s Obsession With Sneakers,” “The Psychology of Sneaker Collecting,” “What’s driving retail’s sneaker obsession?,” and “The History of Sneaker Culture.”

[TotH to friend SL for pointing me in this direction]

* “When you’re accustomed to wealth, you don’t show it, right? That’s why the white kids in school could wear bummy sneakers; it’s almost like, ‘Don’t show wealth – that’s crass.’… As kids we didn’t complain about being poor; we talked about how rich we were going to be and made moves to get the lifestyle we aspired to by any means we could. And as soon as we had a little money, we were eager to show it…” – Jay-Z

###

As we tuck into our Chucks, we might recall that it was on this date in 1975 that Austrian tennis player Onny Parun defeated two-time Grand Slam singles champion Stan Smith in the first U.S. Open match ever played at night. Today Smith is probably better-known for the line of Adidas sneakers named for him.

“There must be quite a few things that a hot bath won’t cure, but I don’t know many of them”*…

New York Knicks power forward Amar’e Stoudemire let the world in on his body-rejuvenating beauty secret via Instagram as this year’s NBA season began: red wine baths… The 31-year-old basketball veteran is soaking his muscles in a blend of vino and water to “create more circulation” in his red blood cells. In addition to red wine, Stoudemire takes a dip in an “ancient tub,” a cold-plunge pool, and tops off his spa session with a massage.

But before you start dumping Two Buck Chuck into your tub, Regine Berthelot, a vinotherapist and treatment manager for Caudalíe Spas in North America, Brazil, and Hong Kong, says that bathing in booze will actually dehydrate your skin. Instead, it’s the extract from the red vine leaf that is shown to strengthen capillaries, stimulate blood flow, and detox the body—a cup of which is incorporated into the Red Vine Barrel Bath ($75) at the brand’s spa at The Plaza in New York City. Polyphenols and resveratrol (a molecule deemed as one of the most powerful antiagers by professor David Sinclair at Harvard Medical School) are other trace elements that can be found in this treatment, although Berthelot says higher concentrations of both ingredients can be found in a simple glass of wine…

While one hopes that Stoudemire found the soak soothing, one notes that that Knocks are in the midst of a disastrous season (8-37 so far, with a franchise record 16b games loosing streak…

Still, readers who want more information can find it at “Why Drink Red Wine When You Can Bathe in It.”

* Sylvia Plath

###

As we practice three-pointers, we might recall that it was on this date in 1973 that UCLA’s basketball team won its 61st consecutive games, an NCAA record, on the way to an undeafeated season and a record 89 wins (and 1 loss) over a three-year span. The Bruins won a(nother) National Championship that season.

The lay of the land…

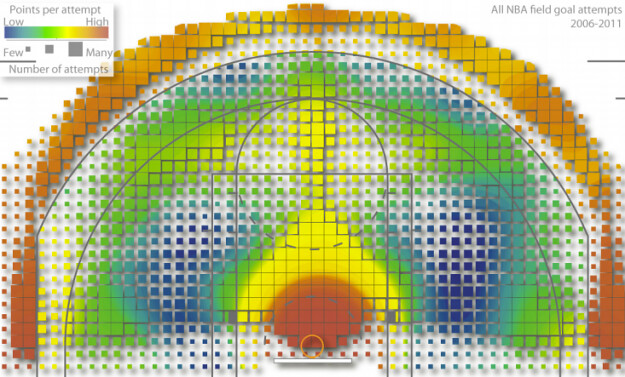

March Madness is here, and the NBA is lumbering through the second half of its season; roundball is all around us. Happily, there are infographics to help…

Kirk Goldsberry, a visiting scholar at the Harvard Center for Geographic Analysis and an assistant professor of geography at Michigan State, has created Courtvision, a series of graphic analyses like the one above aimed at better understanding the battles on the boards.

Readers will find it crammed with insight (e.g., the most effective 3-point shooter in the NBA? Stephen Curry, of Davidson and the Golden State Warriors)…

Perhaps Dr. Goldsberry will follow fellow sport-data geek Nate Silver into politics…

[via Flowing Data]

As we dribble, we might recall that it was on this date in 1972 that the Cincinnati Royals announced the move of their NBA franchise from The Queen City to The Paris of the Plains, where the following season they played as the Kansas City Kings. (Actually, they were briefly “the Kansas City-Omaha Kings,” but “Omaha” was dropped after two years…) At the time of the announcement the Royals– once the home of such greats as Wayne Embry, Jerry Lucas, and Oscar Robertson– were on the way to concluding a 30-52 season and missing the play-offs for the fifth year in a row. It may be evidence of karma that the franchise has, since 1985, been the Sacramento Kings.

Final home of the Cincinnati Royals (source)

Final home of the Cincinnati Royals (source)

… Or should we be celebrating (and using) Tau instead?

You must be logged in to post a comment.